In this podcast, artist Diana Foster and academic Josef Butler discuss the story behind our new art installation, Somewhere to Stay. Diana details her mother’s forced displacement from the family home in eastern Poland in 1940, and the long journey that she took through many countries, as she and other Poles were moved on multiple times across multiple borders, eventually arriving to make a new home in the UK. Josef contrasts his own family’s story, and shares his research on the Polish exile community in Britain, contextualising Diana’s story against the backdrop of a wider set of mass migrations from the 1940s up to today. Together, they help us to reflect on the power of artistic and historical narratives of forced migration to deepen understanding of contemporary experiences of displacement and to disarm the toxicity of current political debates around the so-called ‘refugee crisis’.

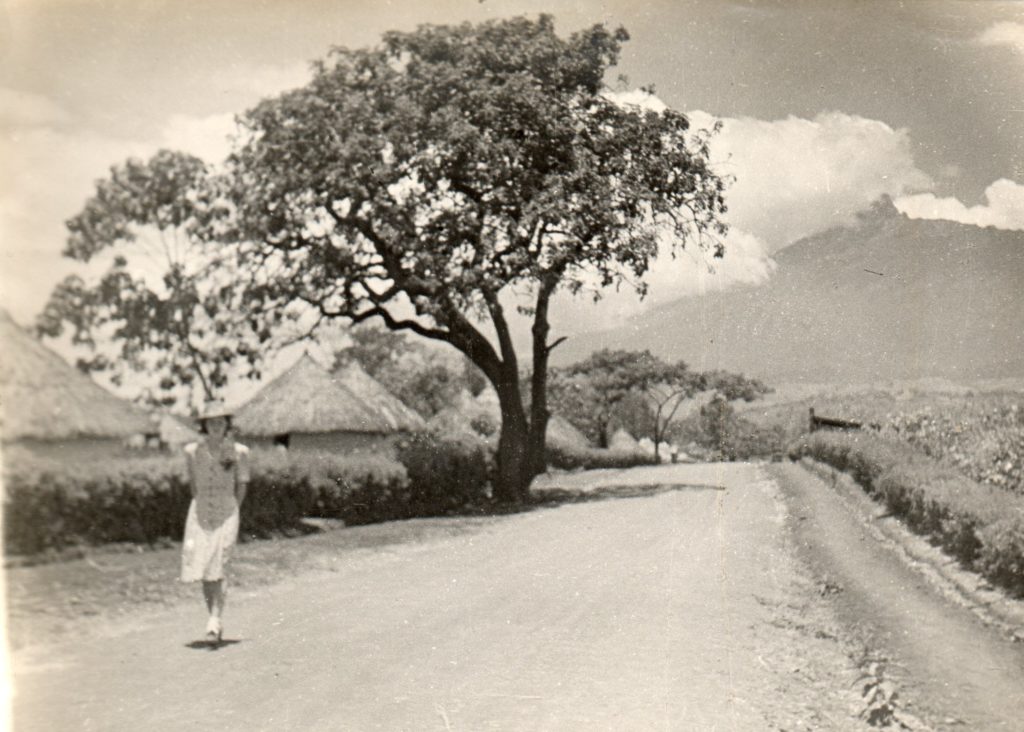

During the episode, Diana discusses her mother’s experience of being deported from her home in eastern Poland (now Ukraine) to a labour camp in Soviet Russia in 1940, and of her arduous journey from there to Uzbekistan, Iran, Tanzania and (eventually) Britain, where her family finally settled. She also talks us through the artwork she has created to help us visualise that journey: in particular, ten laser-cut aluminium panels which depict the different forms of shelter which her mother found herself living in, from wood barracks in the Siberian gulag to army tents, stables, mud rondavels and Nissen huts. As she explains, her art has been inspired the old Polish paper-cutting craft of wycinanki, which allows her to create works that cast shadows, evoking the long shadow of war. Her new art installation, ‘Somewhere to Stay’, was co-commissioned by the Visualising War and Peace project and the IWM 14-18 NOW Legacy Fund, and is on display at Kirkcaldy Galleries (4th Feb-14th May 2023) and St Andrews’ Wardlaw Museum (25th May-30th November). You can read more of her mother’s story here.

Josef helps us understand Diana’s family story in the context of a wide range of Polish displacements triggered by World War II. He underlines the diversity of journeys taken by Polish refugees from east and west, which underlines how expansive an approach we should take to defining ‘forced migration’; and he helps us picture the scale of these population movements, which traversed many different countries across multiple continents. He reflects particularly on the role played by British (former) colonies not only in providing temporary accommodation and resources to Polish refugees but also in shaping their ideas of Britain and British identity. This leads to some fascinating discussion of identity-formation amongst Polish communities in exile, both in temporary camps and in the communities where they settled permanently. Josef warns against ‘flattening’ narratives that homogenise Polish identity and refugee experiences, stressing the ‘messiness’ of Polish identity in exile. He also talks us through the various ways in which Polish refugees were encouraged to integrate with the local population – while sometimes being barred from doing so. Diana shares some of her mother’s experiences of being ‘Pinglish’, adopting many British customs but being unwelcome as a potential new leader of the local Girls Guides because she was Polish.

As Josef underlines, the displacement of thousands of people from Poland during the 1940s was only one of several mass migrations during WWII and in the post-war era. Mention of the Windrush generation and the British Nationality Act (1948) sparks discussion of the different attitudes which different kinds of migrants were met with, and the political labelling (both then and now) of some migrants as ‘good’ or ‘worthy’ (e.g. because they can be of future ‘service’, or because they share common experiences in the past) and others as not. Together, Diana and Josef reflect on the prejudices and hostility which many groups of refugees face, but also on the valuable contributions which they invariably make over time to the communities where they settle. Josef points to the history of many Polish clubs in Britain as an example: originally founded to help Polish exiles preserve cultural traditions, process their shared experiences of displacement and trauma, find a sense of community in a strange new country, and even educate the local population about Polish history, they have become an integral part of British society – most recently playing a prominent role in supporting forced migrants from Ukraine who have been newly displaced. As Josef stresses, while habits of visualising forced migration often deny refugees any agency and demonise migrants for wanting to choose a better life, we should celebrate the fact that thousands of Polish refugees (along with many others) chose to stay in the UK and make it their home.

As this episode underlines, art and history are both valuable media for visualising forced migration with fresh eyes. The history of this particular forced migration from 80 years ago can help us better understand how so-called ‘refugees crises’ play out in the long term, over multiple generations. It opens our eyes to personal and social resilience, adaptation and growth, as well as to the trauma and profound challenges which forced displacement poses to individuals and communities. Diana’s art invites us to engage on a personal level with the story of someone like us; while the wider history that Josef sketches helps us look beyond today’s headlines and learn deep lessons from the past.

We hope you enjoy the episode.