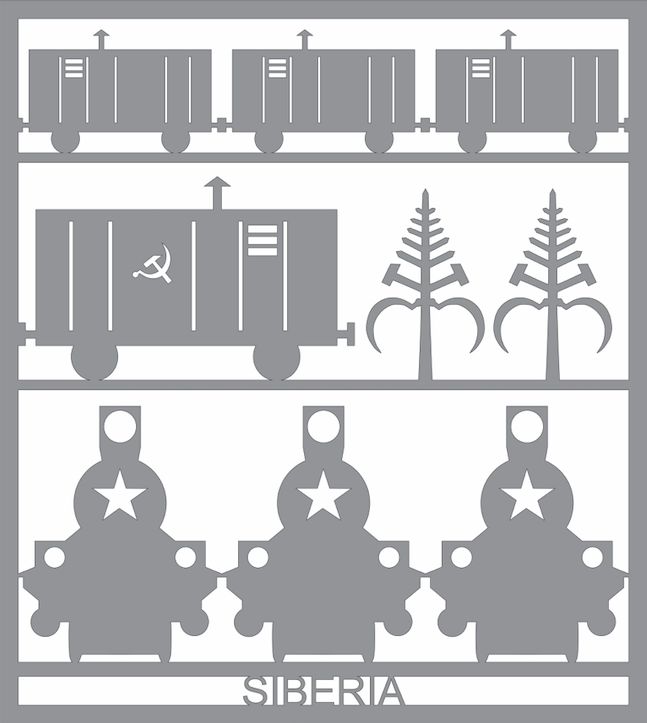

The recent, horrific events in Ukraine echo those of 1940, when Russian troops invaded eastern Poland at the beginning of the Second World War. A million Polish people were forced from their homes at gunpoint and sent to labour camps in Siberia. Artist Diana Forster’s mother, Anna Sokulska Forster, and her grandparents were among them. They were taken from their village north-east of Lviv to a Soviet labour camp in Archangelsk Province.

The journey to Archangelsk was terrible. The deportees were locked in cattle trucks with little food and water, and no idea of where they were being taken or how long the journey would last. Their destination was a logging camp with accommodation in shared barracks. Once there, they were forced to work in temperatures as low as -40°C on a starvation diet.

After about 18 months, detainees were released from the camp under the ‘amnesty’ granted by Stalin when he joined the Allies, following Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union. Forster’s family made their way south through Russia to Uzbekistan, where recruitment centres were being established to form a Polish Army (the 2nd Polish Corps) that would continue the fight against Hitler. Diana’s grandfather and one of her uncles enlisted but conditions in the recruitment centres were very bad, and her grandfather died.

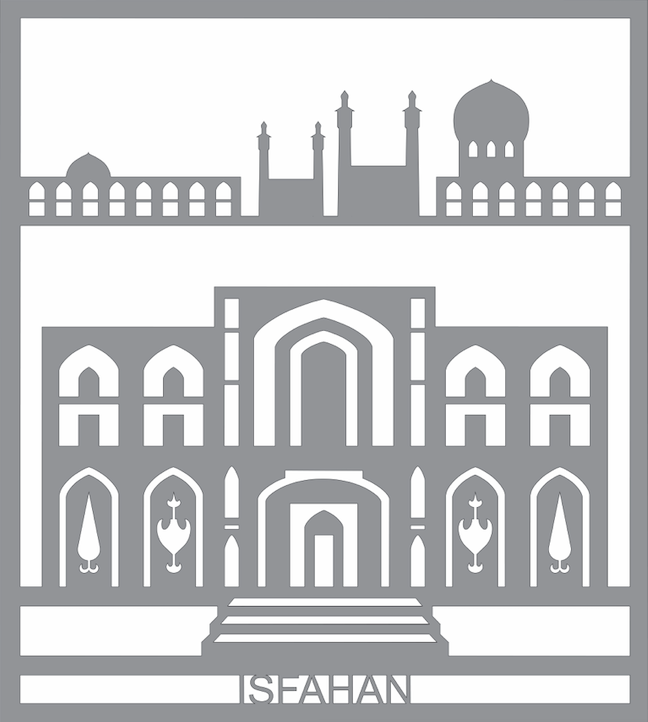

The soldiers and their families left the Soviet Union by crossing the Caspian Sea to Persia (now Iran) and once there they were looked after by the British Army, the Red Cross, and many hospitable locals. There were many orphans whose parents had died in the camps or on the journey and some were very ill; Isfahan was identified as a place with a climate that could help them recover.

Meanwhile, it was decided that the surviving family groups would sit out the war in the British Colonies along the east coast of Africa. The next stage of the journey involved terrifying trips by truck through mountains to India, then by boat from Karachi to Mombasa, and finally inland to a camp that had been established for the refugees in Tanganyika, now Tanzania but then a part of British East Africa. At the end of the war, many of the soldiers and their families settled in the UK, with several large groups staying in Scotland.

Somewhere to Stay focuses on the extraordinary journey and very different kinds of shelter endured by the Polish deportees. Their story is rarely told and has much to contribute to our understanding of the impacts of conflict and forced migration in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Diana Forster’s artwork has always focused on the everyday experiences of ordinary people, and she draws viewers in with beautiful aesthetics, allowing stories to unfold gradually rather than repelling or horrifying us with brutal images. This new commission continues in that vein, depicting domestic objects and ‘homely’ scenes as a way of representing what Polish refugees were forced to leave behind and how they tried to recreate a sense of home at every stage on their long journey.

The laser-cut images of the panels were influenced by the traditional Polish craft of paper cutting (wycinanki). The first panel in particular was inspired by the beautiful paper cuts of Karol Klosowski (1882-1971). The cut-out images make it possible to cast shadows, both through artificial light and sunlight, which add another dimension to the artwork and introduces the idea of the ‘long shadow of war’ – connecting to the Visualising War and Peace project’s wider study of war’s extensive aftermath.

Below, you can see a map that plots the route taken by Anna Sokulska Forster when she was displaced from Poland in 1940; and you can follow her journey through each of Diana Forster’s ten storytelling panels in Somewhere to Stay, starting here with Panel 1. Diana Forster and academic Josef Butler discuss her family story further in this podcast. If you want to find out more about the wider history of forced displacements from Poland during and after the Second World War, you can browse this reading list, kindly provided by Dr Katarzyna Nowak.