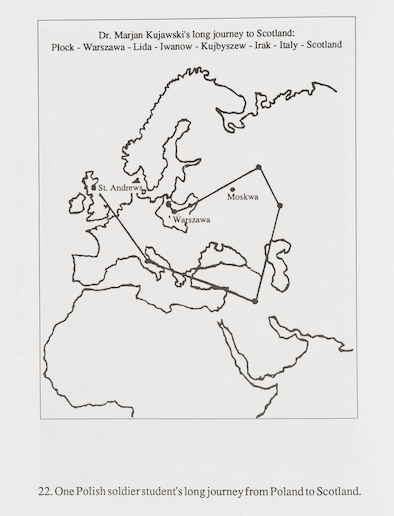

The maps below represent just two of the many thousands of different journeys taken by people displaced from Poland during the Second World War. On the left, we can see the route taken by Anna Sokulska Forster, when she was taken prisoner by Soviet forces and deported from her home in eastern Poland in 1940, aged 16. (This map reflects the political borders that prevail in the 21st century, but of course those borders were very different in the 1940s and they also changed significantly in the post-war period.) The right-hand map details the journey of one Polish soldier-student, Dr. Marian Stanisław Kujawski, from Płock, Poland to St Andrews, Scotland. It was published in Anna Frąckiewicz’s book, Polish Students at the University of St. Andrews: Life and Times of Graduates, 1941-50 (1994), which traces the lives of a range of Polish migrants who ended up in Fife as a result of the war.

Right: Journey taken by Marjan Kujawski, a Polish soldier-student at the University of St Andrews. Image from Anna (Gerstman) Frąckiewicz, Polish Students at the University of St. Andrews: Life and Times of Graduates, 1941-50, published 1994, page 110.

We might be struck at first by their similarities. Like Anna Sokulska Forster, Marian Kujawski appears to have been imprisoned in labour camps in Soviet Russia, before joining the Polish army under General Anders after the Sikorski-Maisky agreement in 1941, as Anna’s father also did. While the initial stages of his migration mirror those of Anna’s family, his military role took him in other directions, landing him in Scotland many years before Anna reached the UK. What he experienced en route and during the long process of adjustment and home-making (as he married a Scottish woman called Sheila, and settled down to pursue academic work) must have differed significantly – as did the experiences of all the individuals chronicled in Frąckiewicz’s book. Between them, they represent a great diversity of migration stories which their shared trajectory on a map cannot convey. In bringing their narratives to life, Frąckiewicz helps us understand how personal circumstances (such as age, gender, family ties, educational background) and individual decision-making shaped these forced migrants’ journeys, alongside many forces outside their control.

Visualising Anna and Marian’s journeys on a map helps to emphasise the distance covered and the sometimes circular and unpredictable movement of displacement. But how do these images resonate with you as a viewer? Plotting such journeys from an aerial viewpoint, with land masses, city/country names and geopolitical borders the only things on view, might distance us from the human experience that is more visceral when displayed in other media, such as Diana Forster’s artwork – or the photographs below.

Right: The Kowalski family travel on foot from the Soviet Union over the mountains into Persia (1942). Credit: Terry Ashwood, Army Film and Photographic Unit. © IWM, item E 19029.

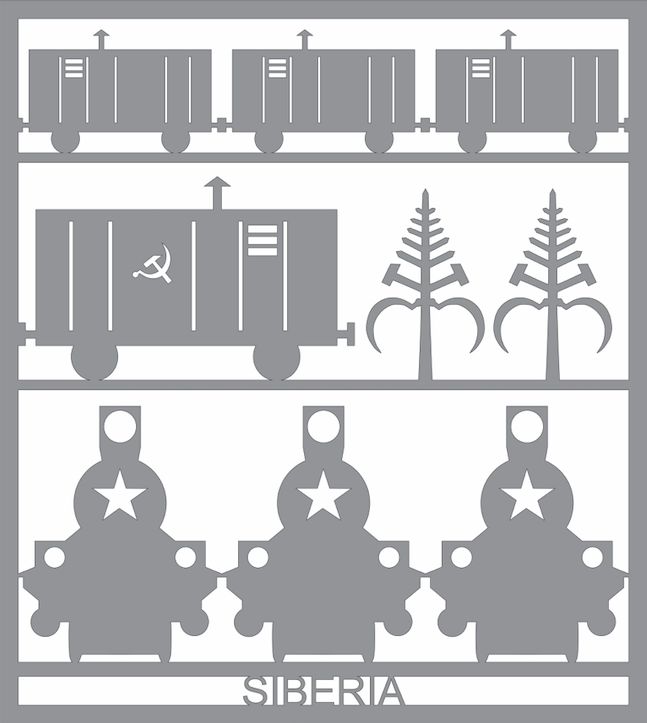

These photographs depict Polish refugees traveling through the mountains separating the Soviet Union from Iran. After the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939, many Polish citizens were forcibly deported to Russia in exile or to labor camps, as noted above. In 1941, after Germany invaded the Soviet Union and Stalin changed sides to join the Allies, Polish refugees were released from captivity. Many journeyed by foot through nearby Iran and to established transit camps which provided food and medical care. The images above, from 1942, portray different elements of the traveling refugee experience.

In the image on the right, the Kowalski family poses on their long journey. This portrait reminds us that multiple generations were displaced together – with the men destined to be separated from the women and children before they had travelled much further (as men were recruited to serve in the 2nd Polish Corps). Carefully posed, they are all holding onto each other, communicating care and togetherness. The beauty of the landscape contrasts with the tough reality of their situation. When that is recalled, the rough rocks in the foreground suggest labour, not leisure. While the girl on the left might be dressed for a day out, the bundles of blankets and the man’s rope belt evoke a different kind of travel. They are looking outwards, to some far-off horizon – suggesting hope, but also the distance they still have to go.

In the image on the left, a group of refugees – mainly women and children – rest on their journey. Again, the landscape is impressive; but the gathering of infants, siblings, mothers and grandmothers looks incongruous against that setting. There are small clusters within the larger crowd, suggesting family units or particular friendships; but the photograph – and the journey – also turns them into a homogenous group, effacing individuality. Many are looking down, perhaps because of the glare of the sun; but there is also a distinct lack of energy. Those looking up are facing the photographer, their gaze focused on this moment in time rather than horizons beyond. An image of rest that evokes tiredness. While people dominate the foreground, the scale of the mountains behind speaks to the vast distance that separates them from anything they can call home.

Above: A party from the Polish refugee camp go out to meet new arrivals – both parties run towards each other (1942). Credit: Terry Ashwood, Army Film and Photographic Unit. © IWM, item E 19034.

This third photograph depicts two refugee groups running towards each other upon the arrival of new refugees at a camp in the mountains. Journeying has become a certain sort of homecoming – albeit to another temporary place of shelter. The outstretched arms of fellow Poles welcome newcomers to an established community, one that transcends location. In their rush to embrace, refugees are reclaiming a sense of shared belonging, culture and identity, as well as a place to rest from their travels. The mountains in the background are very hazy, barely visible – but they are a tangible reminder of how physically far from home everyone in the picture is. The two groups of people coming together in the foreground conjure a different sense of home, reminding us of the power of solidarity and the ways in which forced migrants provide sources of support to each other. Quite different from media images of one-directional queues of refugees at border posts (which imply that asylum-seekers are solely reliant on neighbouring countries for support), this welcome party photograph helps us visualise refugee groups and mass movements in refreshing ways, redrawing boundaries between ‘strangers’ and ‘family’ and modelling the kind of hospitality that can make a place feel like home.

How do these images challenge your perception of refugees and forced migration? What kinds of visual images do you associate with journeys of displacement, and how do these images above fit into that understanding? How do these stories emphasize the geographical scope of a forced displacement (from Poland to Iran and beyond), while also giving glimpses into human stories? And what do these images say about the new forms of family or community that can arise under these circumstances?

You might find it interesting to compare these photographs with the visual journey that Diana Forster’s artwork takes us on, particularly the move she makes from depicting people before displacement in Panel 1 to depicting inhuman methods of deportation in Panel 3. The inclusion or omission of humans from images of forced migration can influence how we visualise the refugee experience in a huge variety of ways.

Left: Diana Forster, Panel 1: Somewhere to Stay (2022). Right: Diana Forster, Panel 3: Somewhere to Stay (2022).