‘With reports suggesting that there could be 25 million to 1 billion climate refugees by 2050, it is critical that this topic is discussed at all levels and in all places – by young people as well as adults. Therefore, I developed a comic story focusing on a young climate refugee in rural Bangladesh, one of the areas most affected by the changing climate.’

Harris Siderfin, ‘The Power of Comics in Peace Education‘ (Museum of Peace, 2022)

In 2022, a group of University of St Andrews undergraduate students developed a research project looking at different approaches to peace education, as part of some wider research into the forces that shape past and present habits of visualising peace. While team members Joe Walker, Margaux de Seze and Otilia Meden compared school curricula, newspapers aimed at children, and mindfulness training, two other students – Harris Siderfin and Maddie McCall – became interested in the use of popular media such as comics as an interactive and impactful teaching tool. Together, they created a short comic strip based around a story of forced migration, as a way of engaging young people with this complex topic in an accessible and human-centered way.

Harris was particularly inspired by the work of Shujaaz Inc, a multimedia youth platform based in Kenya that distributes a free monthly comic, produces radio programmes, creates TV shows, and runs social media accounts based on the popular characters featured in its comics – using Sheng, a contemporary slang favoured by many young people in Kenya. The stories they tell across different media revolve around a 19-year old radio DJ and influencer, living on the outskirts of Nairobi. The DJ uses his media platform to bring young people together to talk about their experiences, the changes they want to make and the barriers that are standing in their way, spotlighting the stories of young ‘shujaaz’ (‘heroes’) who are creating change in their lives. Addressing issues such as gender inequality, reproductive health, human rights, fake news, and political violence, Shujaaz reaches over 9.1 million 15–24-year-olds across East Africa, connecting them with information, skills, and resources they need to take charge of their lives. The Television Academy has recognised the company twice, awarding two Emmys, one in 2012 and another in 2014. You can hear Harris interviewing Rob Burnet, founder and CEO of Shujaaz Inc, about their work and about the power of comics as a medium for education and engagement on this Visualising War and Peace podcast.

Based on Harris’ research into Shujaaz and other uses of the comic form to teach and engage young people, Harris and Maddie created a comic of their own, designed to expand peace education in schools by shining a spotlight on one particularly pressing cause (and consequence) of conflict: climate migration.

Set in a small coastal town in Bangladesh, the comic centres around a young girl called Āśā (meaning ‘Hope’). Her father works as a fisherman while her mother stays at home to care for the family. Āśā goes to school, loves reading, and hopes one day to become a lawyer. But as she grows up, her life becomes increasingly unstable and her dreams are threatened: climate change leads to recurring floods in her home town, which destroy people’s houses and lead eventually to her father’s death. With no source of income or place to stay, Āśā and her family are forced to leave and seek work and shelter elsewhere. The completed part of the comic ends on this cliff-hanger: ‘They join the 19 million other climate refugees in Bangladesh alone…’.

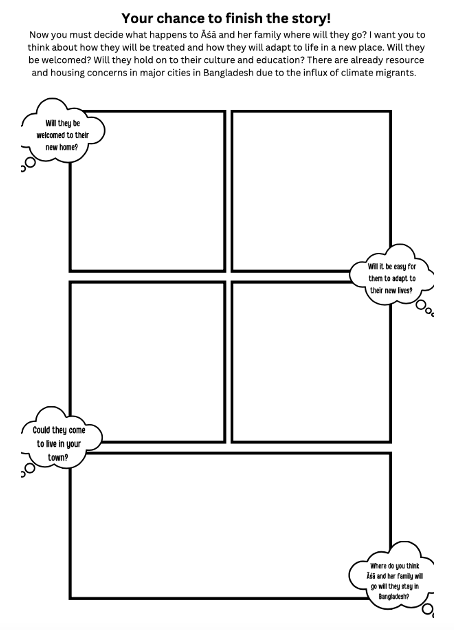

At this point, authors Harris and Maddie hand over the storytelling to their young readers: ‘Your chance to finish the story! Now you must decide what happens to Āśā and her family. Where will they go? How will they be treated? And how will they adapt to life in a new place? Will they be welcomed? Will they hold onto their culture and customs? Will Āśā have the chance to continue her education? There are already resource and housing concerns in major cities in Bangladesh due to the increase of climate migrants. Could they come and live in your town?’

The aim in handing over the storytelling is to help school children actively visualise the challenges which both forced migrants and host communities face in supporting people who have been displaced through no fault of their own. The process of adding new text and images will require dialogue, research, reflection and problem-solving. In working through the dilemma faced by a school-aged child, workshop participants will put themselves in her place, developing wider empathy and understanding. By writing and drawing about forced migration, the children will also develop their own views and learnt to use their voice on a topic that is mostly discussed by adults. Completion of this colourful comic is designed to inform and empower young people, who might go on to change the stories we find ourselves telling about forced migration in the future.

In what follows, Harris reflects on the value of comics as a storytelling medium and as a teaching tool, to introduce young children to complex topics such as forced migration, to help them engage and empathise, and to empower them to have their say.

Harris Siderfin on the power of comics

Media can come in many different forms. Film, TV and social media are arguably the primary sources of information in the 21st century, particularly in the West. However, radio and print media remain very influential, especially in global south countries where energy supplies, internet access and state control of media can disrupt information flows. One form of print media which has garnered significant success in producing peaceful outcomes in East Africa is comics. For example, the company Shujaaz Inc has demonstrated that young people who interact with their media (roughly 9.1 million monthly readers) are 2.4x less likely to have children in their teens, 43% more likely to use contraception and earn on average $21 more a month than non-fans (Shujaaz Research, 2022). Shujaaz gives young people in East Africa access to information that will help them take control of their lives and educate them about the dangers of groups such as Al-Shabaab, a powerful militant group in the region. They mainly conduct this education through comics that have been extremely popular with their readers, demonstrating the efficacy of comics in producing peace. But what makes comics so powerful?

One core strength of comics is that anyone can process information regardless of literacy. Comics have been vital in conflict resolution in areas such as Rwanda, where illiteracy is high; alongside radio shows, comics have educated people about the genocide, helping to build relative peace in the region (Yashmon & Yashmon, 2006). Further, comics can be engaging and uplifting even when the topics they discuss are upsetting or difficult (take, for example, Judd Winick’s 2009 book Pedro and Me: friendship, loss and what I learned). Topics such as genocide, conflict and displacement can be tough to discuss, especially for those with personal experience with these topics. Through the use of satire and humour, complex subjects can become far more accessible (Yashmon & Yashmon, 2006). For example, comics in major newspapers often discuss serious political issues but do so in a way that is humorous to readers. There is much anecdotal information on the power of comics to educate. However, few academic studies have tested to see how effective comics are as an educational tool to teach about peace.

For these reasons, we wanted to investigate how effective comics could be in teaching children about critical peace-related topics, in particular forced displacement. Through school-based workshops, we plan to test the effectiveness of this comic to teach students of various ages about climate migration, investigating how much they enjoyed engaging with it and what they learned, via some before-and-after surveys with both teachers and pupils. As well as being an accessible medium in itself, the comic format has allowed us to create a resource which children can directly interact with – by developing their own endings. As Maddie discusses in this blog, we did not want our comic to look so professional that the workshop participants would feel nervous about adding their own text and drawings; so we kept the artwork simple, and provided speech bubbles to help guide their storytelling. Whatever stories they end up adding in the workshops themselves, we hope that our comic will generate conversation, encourage more discovery and learning, and teach children that visualising forced migration from different perspectives is a crucial step in addressing its causes and in supporting people impacted by it.

You can read the whole comic below.

What do you think?

- How would you end Āśā’s story? What problems would she encounter? What solutions might she find?

- What are the limitations – as well as the advantages – of the comic format, to visualise forced migration?

- In what other ways can popular media such as the comic be used to engage and empower young people on the issue of forced migration?