In 2022, a group of University of St Andrews undergraduate students developed a research project looking at different approaches to peace education, as part of some wider research into the forces that shape past and present habits of visualising peace. While team members Joe Walker, Margaux de Seze and Otilia Meden compared school curricula, newspapers aimed at children, and mindfulness training, two other students – Harris Siderfin and Maddie McCall – became interested in the use of popular media such as comics as an interactive and impactful teaching tool. Together, they created a short comic strip based around a story of forced migration, as a way of engaging young people with this complex topic in an accessible and human-centered way.

Set in a small coastal town in Bangladesh, the comic centres around a young girl called Āśā (meaning ‘Hope’). Her father works as a fisherman while her mother stays at home to care for the family. Āśā goes to school, loves reading, and hopes one day to become a lawyer. But as she grows up, her life becomes increasingly unstable and her dreams are threatened: climate change leads to recurring floods in her home town, which destroy people’s houses and lead eventually to her father’s death. With no source of income or place to stay, Āśā and her family are forced to leave and seek work and shelter elsewhere. The completed part of the comic ends on this cliff-hanger: ‘They join the 19 million other climate refugees in Bangladesh alone…’.

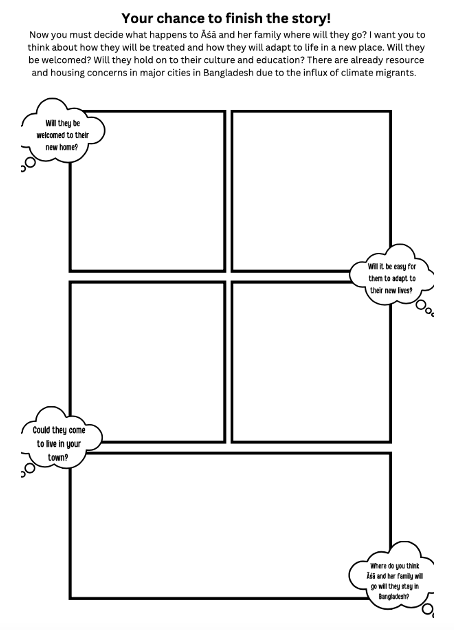

At this point, authors Harris and Maddie hand over the storytelling to their young readers: ‘Your chance to finish the story! Now you must decide what happens to Āśā and her family. Where will they go? How will they be treated? And how will they adapt to life in a new place? Will they be welcomed? Will they hold onto their culture and customs? Will Āśā have the chance to continue her education? There are already resource and housing concerns in major cities in Bangladesh due to the increase of climate migrants. Could they come and live in your town?’

The aim in handing over the storytelling is to help school children actively engage with the challenges which both forced migrants and host communities face in supporting people who have been displaced through no fault of their own. The process of adding new text and images will require dialogue, research, reflection and problem-solving. In working through the dilemma faced by a school-aged child, workshop participants will put themselves in her place, developing wider empathy and understanding. By writing and drawing about forced migration, the children will also develop their own views and learnt to use their voice on a topic that is mostly discussed by adults. Completion of this colourful comic is designed to inform and empower young people, who might go on to change the stories we find ourselves telling about forced migration in the future.

In what follows, Maddie McCall reflects on her creation of the artwork that brings this story to life in comic form, and also on the role of art in the classroom to teach children about complex topics such as forced migration, to help them engage and empathise, and to empower them to have their voice. Harris discusses the power of comics as a tool for visualising and addressing forced migration in this separate blog.

Maddie McCall on colour, emotions, empathy and understanding

“Art provides us with a sense of trust and openness that helps us to be flexible, to be ready to solve problems, to be open to the unexpected; it helps us to connect with our inner feelings, and with the feelings of the ones who surround us. It helps us to feel part of a community.”

Soledad Martínez, Teaching Peace Through Art (2022)

While I was planning the artwork for the comic which we designed to help teach school children about forced migration, I knew that I would not be able to draw complex, detailed panels. At first this discouraged me; but as I read, I came across a great quote by Scott McCloud, who argues that ‘a simple style does not necessitate a simple story’ (Reynolds, 2006). This statement really inspired me to focus on the key characters and moments within the comic. My favorite box is the one of the sinking boat with the father’s hat floating next to it. Through its simplicity it conveys the father’s death (as stated in the text box) but it also creates a powerful emotional response, by seeing all that is left of the father is his hat. I believe that this art of simplicity is effective as a teaching tool, allowing students to imagine all that may be going on in the background and, in our case, the global context of the dangers of climate change and the forced migrations that it triggers. I hope that the simplicity of my drawings is also inclusive and empowering, helping children feel able to add their own drawings to mine as they develop the story and work through how this particular journey of forced migration might end.

My colour choices were based on color-theory and psychology. Colour plays a critical role in learning and in the consumption of media, in addition to the words that images are accompanied by. Research has revealed that all human beings make an unconscious judgment about a person or item within 90 seconds, and between 62-90% of that assessment is based on colour alone (Stone, et al; 2017). Thus, a reader’s first glance at the comic is pivotal in determining the message it is trying to convey. Because the human eye can distinguish between wavelengths, we not only see color, but we feel color. It has biological, psychological, social, and cultural dimensions, all of which give it meaning and the ability to convey information (Stone, et al; 2017).

Drawing on some psychological research on the meanings of colour (Oleson, 2022), I formulated the main colours that I wanted to use for the comic. For the first panel, I made the colours vibrant in order to convey a tone of happiness. I learnt from my research that children are drawn to bold pinks, reds and oranges, which attract their attention to detail. Purple has also been found to grab children’s attention as well, so I dressed the mother and father in purple outfits. I used orange for the main character’s veil because it enhances critical thinking and memory, and when the children reflected on the comic when writing their own ending for it, they would be more likely to remember her clearly as they decided her future.

In the second panel, I used a lot of blue and darkened the sky. Using blue evokes feelings of sorrow (Oleson, 2006), which reflects the tone of the second half of the comic in which the main character’s father dies and the family must migrate to a new place. The drastic tone change that the colors reveal evokes a further emotional response accompanied by the written narrative. I am excited to find out what colours children will use to create the final panel when we run the workshops: whether they will use bright colours in order to show hope for the family, or continue with the blue theme that was prevalent in the last panel.

Visualizing peace literally through art is a growing concept in peace education. Children are able to interact with art and use their imaginations far more than they are able to by only reading. Art allows children to sympathize with the concepts drawn and can enhance their general empathy and understanding of peace, conflict and conflict’s many different legacies – such as forced migration (Martínez, 2022). In drawing this comic, I also drew objects and scenes that children could immediately connect with, such as visuals of family and school. Concepts of forced migration can be very difficult to grasp for children, and by simplifying such intense topics to show them that these migrants are just like them will most likely leave a lasting impact on how they react to further discussions on issues of climate change and the impact that it has on kids just like them.

You can read the whole comic below, and find references to my underpinning research at the end of this post.

What do you think?

- How would you end Āśā’s story? What problems would she encounter? What solutions might she find?

- What colours would you use – an optimistic palette or a more pessimistic one?

- In what other ways can art and creative storytelling be used to engage young people with the issue of forced migration?

References

- Oleson, J. (2022) Color psychology: Child behavior and learning through colors, Color Meanings. Available at: https://www.color-meanings.com/color-psychology-child-behavior-and-learning-through-colors/ (Accessed: November 22, 2022).

- Martínez, S. (2022) Teaching Peace Through Art, Peace and Justice Studies Association –. Available at: https://www.peacejusticestudies.org/chronicle/teaching-peace-through-art/ (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

- Reynolds, G. (2006) Learning from the Art of Comics, Presentation Zen. Available at: https://presentationzen.blogs.com/presentationzen/2006/09/learning_from_t.html (Accessed: November 23, 2022).

- Stone, T., Morioka, N. and Adams, S. (2017) Color design workbook: A real world guide to using color in graphic design. Quarto Pub Group USA.