Words are a dangerous game. They don’t just describe a reality; they also create it. At the same time, words are one of the most powerful tools we have at our disposal to change dominant, dehumanising, migratory narratives.

‘The Language of Migration‘, Sitholé, Crawley, et al. (2022), Zanj: The Journal of Critical Global South Studies: vol. 5.1, pp. 14-26

As the authors of the article ‘The Language of Migration’ (cited above) note, ‘When we write for a particular journal or audience, we often default to the dominant ways of representing migration linguistically without stopping to consider whether these meanings are the same for others.’ But if we pause for a moment to scrutinise the linguistic building blocks which shape our worldviews (and people’s fates), we can enter a rich space of new learning, where assumptions are overturned, prejudices are challenged, and migrant experiences change for the better.

A key premise at the heart of the Visualising War and Peace project is that stories are world-building. There is a constant feedback-loop between narrative and reality: the tales that we tell and the pictures that we paint reflect reality, up to a point, but they also help to shape it by influencing how we think, feel and behave. This is true not simply of complex stories but also of very simple ones, which come packaged in single words and phrases. In their discussion of the ways in which different languages articulate, frame and evaluate ‘migration’, Sitholé, Crawley, et al. write: ‘language affects not only how migration may be explained or described by different peoples, but also how migration is inspired, experienced, imagined and reimagined.’ In other words, language affects experience and behaviour, not just understanding, both now and in the future.

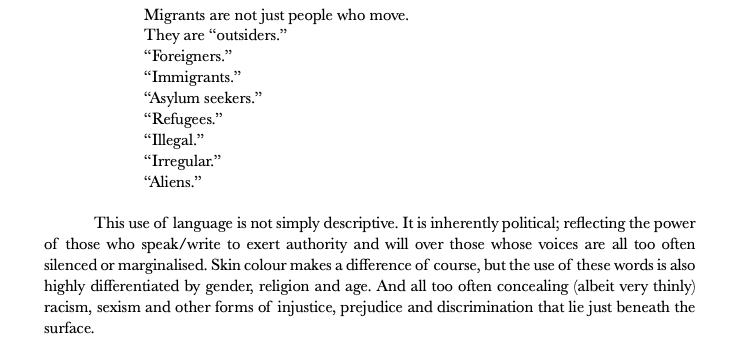

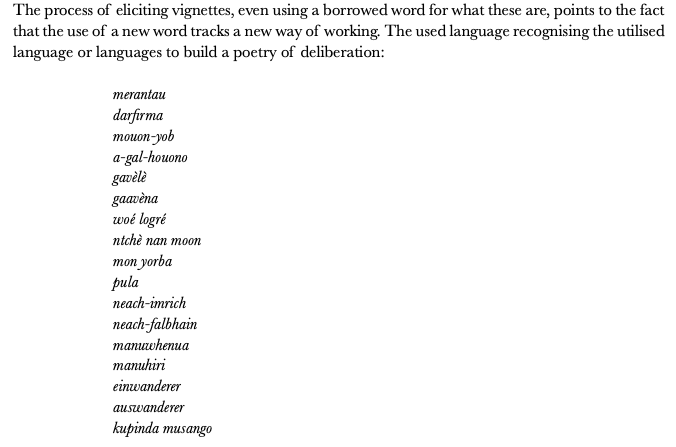

By exploring words and phrases from a range of languages used in Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, Malaysia, Zimbabwe, Scotland and elsewhere, Sitholé, Crawley, et al. unlock a wealth of ideas and associations that help us conceptualise ‘migration’ in many new lights. As a natural ‘ebb and flow’ of people, part the ‘natural order of things’; as ‘strolling’, or ‘wandering’ (often with a view to ‘returning’, circular-fashion); as being ‘in the bush’, which is the opposite of being ‘at home’; as ‘adventure’, even a rite-of-passage for young people; as ‘person-flitting’ or ‘human locomotion’. They look at more sinister uses of (colonising) language to categorise and control, to marginalise and exclude, to delegitimise and dehumanise; and they point to the difference that just a few letters in a word can make (ex-, im-, in-, out-, il-legal, un-documented…). But they also offer forays in multilingualism as a simple yet powerful solution, an inclusive form of wor(l)d-building that privileges nuance over simplification.

The words “migration” and “migrants” clearly have multiple meanings. Many of these meanings and the different ways of understanding the movement of people are flattened out in “migration studies,” which typically reduces migration to the process of movement itself or presupposes that money alone is the reason why people move. In so doing, there is a tendency to ignore the cultural, geographical and historical contexts within which movement takes place as well as the deeply personal, symbolic, ritualistic, emotional and other meanings with which migration is associated – for the individual, family, community and wider society. …Whilst it is difficult to get away from using these terms as shorthand, we need to be cognisant of their power to control and contain, to limit our thinking, to reproduce inequalities in how we understand and represent migration. Reducing the inequalities associated with migration requires us to think, talk and write about migration in more nuanced ways. The terms “migration” and “migrant” mean very different things to different people, in different contexts and at different times. The term “people on the move” is increasingly being used as a way of moving us away from the connotation of migration as a thing, an event or a process, towards a view of migration simply as an activity – perhaps just an ordinary activity, perhaps even a natural one.

‘The Language of Migration‘, Sitholé, Crawley, et al. (2022), Zanj: The Journal of Critical Global South Studies: vol. 5.1, pp. 14-26

You can learn more in this this podcast interview with Alison Phipps, Professor of Languages and Intercultural Studies at the University of Glasgow and UNESCO Chair in Refugee Integration through Language and the Arts. Alongside her academic work, Alison is Co-Convener of the Glasgow Refugee, Asylum and Migration Network, an Ambassador for the Scottish Refugee Council, and she also chairs the New Scots Core Group for Refugee Integration in partnership with Scottish Government and the Scottish Refugee Council, among other high-profile advocacy and policy-making roles. In the podcast, Alison talks about contemporary discourses of migration, in particular the dehumanising tropes that are used to generate fear and a sense of threat (‘swarms’, ‘invasion’, ‘floods’, etc). She reflects on the importance of decolonising the language we use to talk about refugees and asylum seekers, and she helps us see the immense value of going to other languages to explore how they visualise and articulate migration and mobility. As discussed above, words are world-building; but the complexity of meaning that we find when we compare expressions in different languages helps us to nuance our understanding and rethink the attitudes that our own words embody. This in turn can help decontaminate hostile discourses and de-escalate the wars being waged against people whom we are taught (by news headlines and political rhetoric) to feel afraid of.

The Little Letters That Make a Difference, Heaven Crawley

Am I a patriot?

Or an ex-pat?

A migrant?

Or an im-migrant?

Traveller?

Nomad?

Alien?

From this world

But not

It’s the little letters that make the difference.

Ex-

Im-

Out

In

Il-legal

Un-documented

The small words that set us apart

That tell others

Who or what we are

Even when we don’t know ourselves

The little letters that mark us out

That tell others

You do not belong

You are not “native”

You are “stock”

“Migrant stock”

As in “the number of migrants in a given area on a certain date”

As in “the store has a very low turnover of stock”

As in “the value of the company’s stock rose by 40%”

As in “all cattle other than beef cattle and steers over three years of age”

“Migrant stock”

Like cows

Or money

Or goods

Herded

Corralled

Invaluable

But not of value

And then there is

The shock

Of too much stock

When the numbers go up

Not down

When the colour is not white

But brown

It’s the little letters that make the difference.

We are grateful to Prof. Phipps for generously sharing links to her work and that of other scholars in this important field of study:

- Phipps, A. (2019) Decolonising Multilingualism: Struggles to Decreate. Series: Writing without borders. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781788924054

- Phipps, A. (2013) Intercultural ethics: questions of methods in language and intercultural communication. Language and Intercultural Communication, 13(1), pp. 10-26. (doi: 10.1080/14708477.2012.748787)

- Phipps, A. , Aldegheri, E. and Fisher, D. (2022) The New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy: a report on the local and international dimensions of integrating refugees in Scotland.Project Report. University of Glasgow.

- Phipps, A. (2022) Against Capture, Cleansing and Extraction: Towards a New Eco-Social Discourse of Research and Investigation. [Website]

- https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000382874

- New Scots Research Report