The following testimony is one of several stories of forced migration gathered by Research Fellow Dr Diana Vonnak. Inna is a school psychologist from Vyshhorod, Kyiv region. We are very grateful to her for sharing these reflections with, to help us better visualise refugee experiences. TRIGGER WARNING: this article contains details of a shooting.

‘Somehow back then I thought I want no photos, I want nothing, so that I can just eject all this from my memory. And now I sometimes I feel like I would want to look though images from then.’

Inna, from Vyshhorod, in conversation with Diana Vonnak

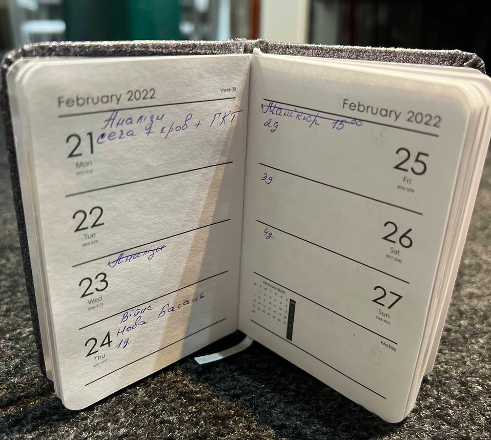

Inna is a school psychologist from Vyshhorod, Kyiv region, and a young mother, having given birth in spring 2022 to her first child, a little boy. In the weeks leading up to the birth, she survived air raids, Russian occupation, and all the challenges of being displaced within her own country. She did not keep a diary, or take any photos or record her experiences in any other way. The single object she has from this time is her small planner, where she wrote down a few important details that she wanted to remember about giving birth under such conditions. Photographs stop in late February, and resume in April. She says she thought it would be easier not to dwell on memories if her mind had no external aides.

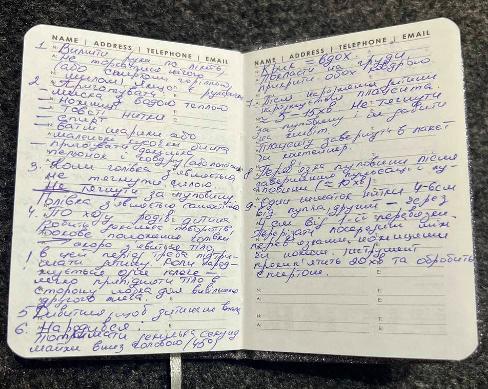

Right: The only entry in Inna’s planner details first aid steps in case she has to give birth without medical care. Resuscitation, stabilisation of breathing.

Inna’s story. Living through occupation

Inna and her husband had just moved to their newly renovated apartment in Vyshhorod, near Kyiv. Originally from Nizhyn, north of Kyiv, close to the border with Belarus, they set out to start a new period of their lives: Inna was pregnant, they were expecting their baby in April. Their new flat was not far from a unit of the Ukrainian National Guards, so when they woke up to the sound of rockets and understood that the war had started in February 2022, they knew that it was better not to stay there. Military objects would be targeted. After a failed attempt to leave towards Rivne in the west, when the road ahead was already destroyed, they turned back and went to Nova Basan, a village northeast from Kyiv, where Inna’s husband had friends who offered to host them. On 28 February, the Russian Army occupied the village.

‘There were very loud explosions, then I saw a plane fly over. When this happened, when planes were flying that morning, I started to run. My husband grabbed my hand and asked: “Where are you running?” I said “I don’t know, I have no idea.” You know, it’s a kind of automatism, it was just too close and very-very loud.’

When the occupation started, they didn’t have electricity for two weeks. They were lucky: their heating used gas. Later the gas went away, but electricity returned from time to time. They had no news from the outside world in those first weeks, when eventually they managed to turn on an old radio. When electricity was on, they had some internet again. Inna sewed all the savings they took with them into her trousers, and wore them day and night. When the Russians arrived, a local man with severe mental health problems, probably schizophrenia, went up to them, and the soldiers shot him dead. His body lay on the street the whole time; they did not allow locals to bury him.

Inna and her hosts was luckier. The soldiers came to the house a week into the occupation. Locals already knew that the soldiers were going around houses confiscating phones. By then they had taken anyone with an army background, members of the local territorial defense forces, and anyone who worked for the local administration. It seemed like they had lists of the people they wanted. Three soldiers came to them on foot, but they were very young.

‘It was visible that these were not mercenaries, they did not behave like professional soldiers. They were young kids, 23 or so. I went out and started to cry very strongly. I put my hand in front of my husband, and shouted at them: “Guys, what are you doing, for what are you doing this?” And they looked awkward and tried to calm me down. They even said sorry, that’s how you know they aren’t professionals. They went on, searched for phones.’

The village where Inna and her husband were staying was very lucky compared to the majority of nearby settlements. There was only occasional physical violence, and the occupying army did not set up camp in local flats. They took valuables from many houses, and there was vandalism, but this particular unit did not engage in war crimes in the ways that have been documented from Bucha, Hostomel and many other occupied settlements around Kyiv.

Days would pass without Inna leaving the house. Even when rocket attacks stopped, she thought it was safer not to be seen, not to interact with soldiers. They had water from a well in the garden, so their house was frequented by neighbours who came to fetch water. Days were short and dark, and there was not much to do. First they had some crosswords, but they soon ran out. Inna tried to sleep as much as possible, cutting herself off of the outside world, to protect her baby from being exposed to everything.

When the Ukrainian army arrived, and locals saw the Ukrainian flag on the first tank, they did not dare to believe it was indeed their own army; when the Russian tanks had rolled in, they all sported Ukrainian flags. [This is a war crime.] Only when they heard soldiers speaking Ukrainian did locals dare to believe, and many ran to the newly arrived soldiers. Inna hugged a woman soldier. It was one of the very few moments she found herself weeping.

Fear of hunger, memories of kindness, and simplicity

‘Somehow these people, they had been practically strangers, my husband knew them, but I met them once in 2018, that was all, but they became like family to me.’

Their hosts in Nova Basan made space for Inna and her husband, giving up their own bedroom and allowing her to have as much comfort as possible. In the end, they spent most of their time hidden away in the backrooms of the house, further away from the road, where it felt safer.

Hunger is a topic that Inna keeps returning to. As she recounts her story, food becomes more and more central, and her memories loop back to last crumbs of a bread-loaf, the small piece of chocolate she was gifted, and the single gulp of leftover brandy she allowed herself when nearby explosions would not stop.

‘When we are understood that they are not going anywhere, we started to economise on food. We decided to just eat twice a day. We didn’t know how long they will be there. A week? A month? Half a year? Nobody knew.’

Locals went to the closed supermarket after a while, but there was little left after the Russian army had looted it. They started to take food for themselves. Her neighbour went, returning with packets of dried goods, and said she left a note on the till explaining what she took, hoping she will pay for it when life returns to normal. Others followed suit, or simply took whatever they could. It was only after three weeks that they were able to start going around the village, to get eggs and milk from those locals who had any to give away.

When food was scarce, Inna’s hosts would pretend they were not hungry, forcing her to eat. ‘Of course I understood what they were trying to do. They were helping my baby.’ She jokes: ‘When I went to the doctor before to do a test for gestational diabetes, it turned out that I do have it, and I was told I must not eat any sweets. In a way it was one of the benefits of occupation that there was nothing like this to eat, so there was no temptation at all.’

Now it has become one of the biggest sources of stress for her if she has food to throw away. They freeze even the last piece of bread if they can’t eat it. ‘I had not known what hunger was. And then when you live through it, in the twenty-first century, you live through real hunger.’

Inna’s pregnancy

Inna was due to give birth in April 2022. Her pregnancy exposed her, changing how she thought about risk and the future — and it also changed how others treated her. The care, attention, the small acts of kindness she experienced helped her live through weeks of fear and isolation, but they could not crowd out the reality of the imminent end of her pregnancy in an uncertain future.

As time passed, she grew worried about her prospects. After her first encounter with the Russian soldiers, weeks passed when they did not know anything about the Ukrainian army’s chances. When the electricity returned and they could occasionally look at news and talk to friends or family, they felt more hopeful about possible green corridors, but still they were not sure what to expect. About a month into the occupation, Inna thought that she needed to find a way out, that it would not be safe to remain. She went to a soldier, asking to be allowed to leave for a hospital, but she was curtly refused. When she tried again, she was advised to find a specialist of herbs, any kind of local healer. ‘What kind of places are they from if they think you need this instead of medical care?!’

When the Russian army was starting to retreat, they offered her the chance to travel in a military car to the nearest hospital, but they would not allow her husband to accompany her, or to use their own family car. It was all chaotic then, but locals started to suspect that the army was being pushed out: they were going north day and night in unusual numbers. Inna was given a few minutes to decide, and, not knowing whether she could trust them, she declined. The Ukrainian army successfully retook Nova Basan a few days afterwards.

Inna felt that she did not want to give birth abroad, so she searched for a city in Ukraine away from the frontline, where she would be safe. It was very difficult to find anything, as the cities in the west swelled with millions of internally displaced people, and finding accommodation or medical care was a challenge. She finally managed to register at a hospital in Rivne, where her son was born, and she was relieved to find out that he was healthy.

‘Now that I talk about this, I don’t feel anything, I just speak. But it was difficult then. All these explosions, and I am not a doctor, I don’t understand what goes on inside [the womb]. I used to put pillows on my belly so that I won’t traumatise him with the sounds. We then called him Mykhailo because I prayed to Saint Mykhailo endlessly.’

Scotland

Not long after the birth, Inna, her husband and their infant child set out to Poland, where a charity helped them with temporary accommodation. Her husband had once spent a few months in Scotland with a summer visa that allowed him to work on a berry farm, and he felt that this could be a good, safe place to head for. So they applied to the Scottish government’s Super Sponsor Scheme for Ukrainian refugees and were given visas promptly. They were sent first to Aviemore, but Inna’s husband felt the need to work after months of forced inaction under occupation, and he succeeded in finding a company ran by Lithuanians, where he could rely on his Russian language skills and learn the job faster. They now rent a place in Livingston, which Inna finds very calm. With her child they walk every day, often for hours. When it rains, they stroll in Livingston Centre, the huge shopping mall at the edge of town.

Safety, security, and the legacy of trauma

‘When we left, I had not much stuff. A coat, shoes, two pairs of socks. Same for my husband. Each had a pair of trousers, a sweater. And you realise how unimportant this all is, that you can live without stuff for a very long time, and it doesn’t matter much. Nothing is so important. It is difficult to convey that emotion when you set out to leave, we were going through all these block posts, then they searched us very carefully, because we were coming from the deoccupied territory, we were going through all these destroyed, ruined places. And for ten minutes it was scary, then we started to see people walking on the streets, shops were open. We had not been anywhere, absolutely did not go anywhere. We were a bit wild, I was scared of everything, even entering a shop; now it is all fine, but then I was scared.’

When Inna first arrived in Scotland arrived, she carried so much fear in her that she thought nuclear war could happen, and that it could even reach the UK. Over time she found a greater sense of calm and was gradually able to regain her inner peace. People have been very forthcoming and she feels strongly supported. She thinks about her future living with these memories: time to time something unexpected triggers her into crying, but she mostly feels at peace. It might return, and she will have to work though this experience at some point; at least that is what she expects, but she does not yet know what shape this will take.

‘I think this swims somewhere inside you. Your brain thinks it is all fine, but your body knows better. The brain can’t pretend forever.’