Dijana Muminovic is a Bosnian-American documentary photographer. As she recounts in this podcast episode, she was 9 years old when the Bosnian War broke out in April 1992, and her childhood was dominated by the conflict. She vividly remembers the day it started: out picking flowers, she heard the first siren, followed by a sound that she would quickly learn was the noise of a bomb; and she ran to hide for the first time in the family’s basement. That routine became part of her childhood for the next four years: lots of time hiding in bomb shelters, and coping without electricity and water, with shortages of food, and with constant fear and anxiety, while dreaming of peace.

Dijana grew up in Zenica, an industrial town about 70km north of Sarajevo. Unlike the capital city, it was not a key target during the war; in fact, Zenica became a place to which people from other towns and villages fled. People whose homes had been bombed or burnt, and in particular many Bosnian Muslims who had become targets of ethnic cleansing. Dijana remembers her school becoming a shelter overnight, with the gym crammed full of people. That was her first introduction to what the term ‘refugee’ meant.

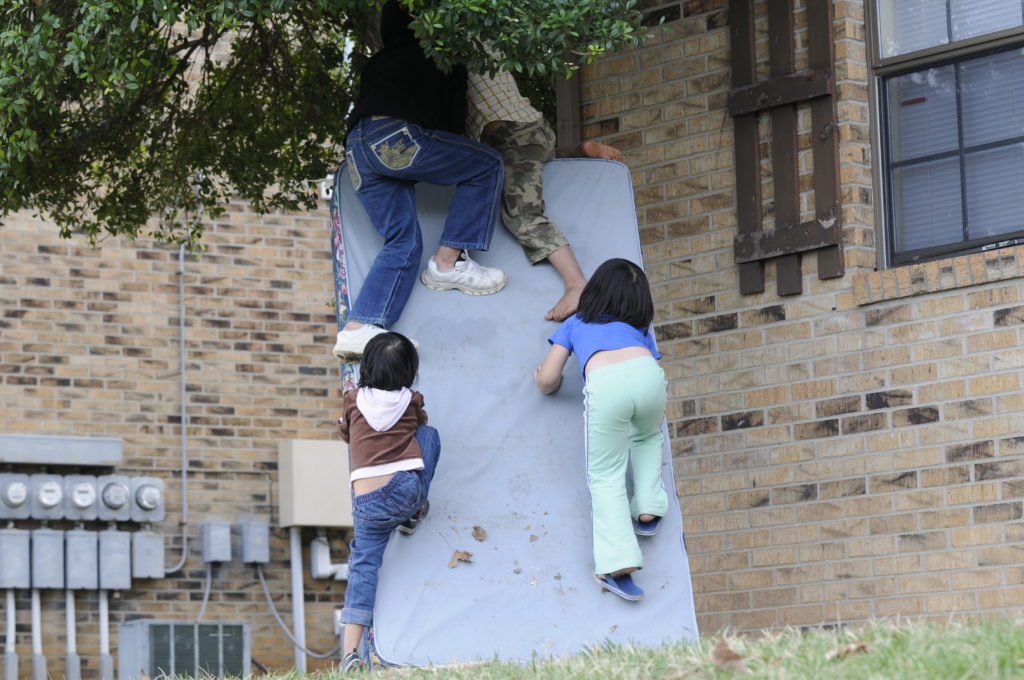

As the war went on, more and more of Dijana’s friends left. As she explains in the podcast, the most difficult moments for her – beyond the terror of the bombs – were learning that another person had been killed or another person had fled. Eventually, Dijana and her family became refugees themselves, leaving behind their home and loved ones and travelling to the US to build a new life. As she explains in this essay, for years Dijana hated the label ‘refugee’: ‘Refugee was that old mattress I slept on my first year in the United States. Refugee was the basement I hid in while planes dropped bombs on my town. Refugee was as dirty as my school where refugees slept…’ Over time, however, she came to look back with pride at her journey from Bosnia to the US, and she became interested in documenting other people’s stories of forced migration.

Some of Dijana’s photographic work has focused on the aftermath of conflict in Bosnia itself (you can see some of her Aftermath photographs here, and read more about them here). She has also produced a series of photographs capturing the lives of immigrants and refugees in Bowling Green, Kentucky, where she herself ended up. This post focuses on two other projects she has undertaken, one documenting the arrival of Syrian and Afghan refugees in 2015 at the Hungarian-Croation border, and the other reflecting on the experiences of Ukrainian refugees in Medjugorje, Bosnia and Herzegovina, in March 2022.

On September 19, 2015, I watched Middle-Eastern refugees and migrants being dropped off by bus at the Hungarian-Croatian border. Reporters lined up, waiting for the doors to open. I thought about how many times these people faced border crossings. Since leaving their homes, they cross at least four countries on foot before reaching Croatia, and at each border the media ‘attacks’ them. I distanced myself from the rest of the photographers. I looked at faces through the window, wanting to find that one person I could connect with, that would trust me and not be annoyed by my camera.

Dijana Muminovic, I’m a Refugee

Having been a refugee herself, whose own journey started with a bus ride from Bosnia to Croatia, Dijana felt great empathy with the forced migrants whose arrival she was watching. As she explains in our podcast conversation, she tries to strike a balance in her photography between documenting what is happening and responding to the people involved as fellow humans. She works hard to build trust with the people she hopes to photograph, rather than snapping images right away – both to avoid exploiting them and to ensure that she learns enough to be able to do justice to their full story.

In the images above, Dijana helps us visualise the labour of journeying, both through movement and moments of rest. Through the rapport she has built particularly with the children in each photograph (she identifies especially with children in these situations, having been a child refugee herself) she helps to humanise the experience. Rather than a crowd of adult backs and heads, all moving anonymously forward en masse, the pink top of the little girl draws our eye in the image on the left; and her gaze into the distance, from the shoulders of a parent, helps us to see things from her perspective. Her pose is both curious and vulnerable, as she looks out at an unfamiliar landscape and into an uncertain future, cuddling a toy. To her left, a little boy looks back at the camera. Though safe in his mother’s arms, he holds her tight; and his expression conveys wariness and perhaps a little anxiety. As the adults press forward, his face asks big questions: what is going on, and where are we heading? The children in the photograph on the right appear more light-hearted and engage playfully with the photographer, reminding us to look at forced migrants as people not victims – ordinary families, having a snack on a grass verge. Some sit, some stand, capturing the temporary nature of this moment of rest. The light streaming into the photograph infuses the picture with warmth, a deliberate rejection of the grim aesthetics of many images of forced migration.

In the photographs above, Dijana has captured something of the lack of control that forced migrants experience as their journeys are managed by officials, policies and systems. The dynamic hand gestures of the railway guard in the image on the left contrast with the folded arms and long-distance gazes of refugees in the train who are being transported somewhere new, able to do little but watch from the window as their destination is decided by others. There is a strong them-and-us dynamic, but our visual proximity to the refugees’ faces helps us empathise with them and look at the guard and the situation through their eyes. In the photograph on the right, Dijana has used reflections in a train window to bring faces into focus, helping us to see individuals in the crowd. Again, their facial expressions and the direction of their gaze communicate the uncertainty they face as they wait to see where they are travelling to.

Several photographs in Dijana’s collection get us looking at the barriers that forced migrants face on their journeys, both physical and metaphorical. The darker side of these images reminds us that refugees are often blocked, hemmed in, imprisoned and even criminalised by the authorities they encounter on their journeys. But the photograph on the right is more illuminating: behind the no-right-turn sign, refugees can be seen turning right. Barriers have to be overcome, and rules that apply in normal times cannot be applied so rigidly in the context of forced migration. Whatever the obstacles, ways must be found – routes to safety, security and a new home.

Amid weariness and worry, there is caring and hope, as the photographs above and below underline. The image of the boy running with some sheaves of corn in his hand reminds Dijana of the hunger she herself experienced, and it also captures a child’s optimism that he can solve the challenges that he and his family face in their life on the move.

When the first 300 women and children arrived in Medjugorje, Bosnia and Herzegovina, in early March 2022, their exodus was reminiscent of the 1990s Bosnian War when 2.2. million people fled the country. In the first few weeks of the Ukrainian war, 4 million women and children were forced to leave their homes.

Dijana Muminovic, From Ukraine to Medjugorje

So begin Dijana’s reflections on her photographic project documenting the reception of Ukrainian refugees in a small Bosnian town that had itself seen war and forced migration thirty years previously. She was struck by the warmth of the welcome offered to these new refugees, and of the sense of community amongst the Ukrainians themselves and between Ukrainians and locals. But she also wanted to capture the limitations of the help that anyone can offer people who have fled conflict. As she put it, ‘Their tears spoke of the torture and hardship during each mass. Will they receive a phone call that their husbands and sons are no longer alive? Was someone else in the family killed, tortured, or raped? The locals in Medjugorje did so well hosting and providing services for everyone, but the women could not stop thinking of their husbands left behind.’

Right: Boy protests in Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina in support for Ukraine (2022); Dijana Muminovic

Medjugorje is a place of pilgrimage for Catholics, and religious worship offered important community-building opportunities for the Ukrainian refugees while they were hosted there. Dijana used religious locations as the backdrop to several photographs to capture the ways in which refugees are often caught in a limbo between light and shadow, hope and fear, shelter and homelessness. Her primary audience, she explains, is people who cannot see past the label ‘refugee’ and who have been influenced by anti-immigration coverage in the press and in politics. As Dijana’s work underlines, photography can play a powerful role in building empathy and deepening understanding of the causes and consequences of forced displacement.

To hear Dijana reflecting more on the ethics of photographing displaced people and forced migration, and the challenges of balancing the duty to document with a more humanitarian role, to provide a welcome and offer support, you can listen to our podcast conversation below. You can read more about her own journey of migration here.