As discussed in ‘Somewhere to Stay‘, Anna Sokulska Forster’s childhood changed abruptly when Soviet troops arrived in Eastern Poland in February 1940, as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which divided Poland between the two powers. The Soviets arrived with lists of people who were deemed to be enemies of the people and who were to be deported to labour camps in Siberia. These lists included soldiers who had fought against the Russians (like Anna’s father), teachers, priests, professors, scientists, and lawyers, together with their wives and children. Those who were to be deported were woken very early on 10 February 1940 by Soviet troops knocking on the door. Sixteen-year-old Anna, four of her siblings who were at home, and her parents were given a couple of hours to collect together a month’s supply of food from the loft, warm clothes, bedding, personal valuables and any money they had. Anna was sent into the loft to collect the food and never forgot the soldier standing at the bottom of the ladder with a bayonet fixed to his rifle. She packed her Polish National costume with the clothes. The family had to leave behind their dog and hope that someone would look after him. Their home and the entire small holding on which they had worked so hard was turned over to the local authority.

Anna’s family was taken first to the school and from there by sledge to the train station in Radziechow, a nearby town. There they were packed with other families into overcrowded cattle trucks lined with wooden bunks, and the doors were locked. The train set off for a journey of about three weeks in freezing temperatures. They didn’t know how long they would be on the train or where they were going. In the evening, when it stopped at a station, the door bolts were removed and a few men from each truck emerged under guard with buckets to collect water and sometimes bread and soup. Toilet arrangements in the trucks were a hole in the floor which the deportees screened off as best they could. People who had been living comfortable, happy, secure lives just a few days before had been stripped of all control and were now subjected to unspeakable conditions by people who did not care about them and would make all the decisions about their future lives. The numbers are disputed but it is estimated that 17,206 families (89,062 people) were deported from Eastern Poland in this way on 10 February 1940.

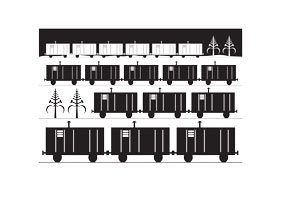

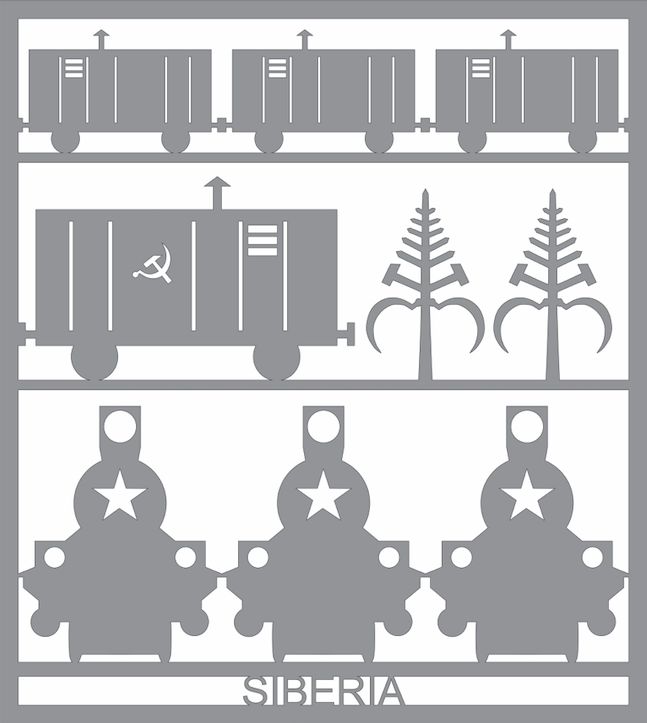

Diana Forster has responded to this aspect of her mother’s migration story in several ways. She has created stark, monochrome images of the ‘train to Siberia’ such as the picture at the top of this page – and also the design for Panel 3 in ‘Somewhere to Stay’. Rows of engines and carriages combine with Soviet symbols to express the power of the occupying force. No people are visible: they have already been swallowed up inside the faceless locomotives.

Right: Here you shall live! (Giclee print, 84.1cm x 118.9cm): Diana Forster, 2020. Translation: ‘Siberia! HERE you shall live!’

Inspired (or provoked) by Russian propaganda posters (such as this and these, designed in the early 20th century to celebrate the Russian Revolution), Diana has also created more colourful, deeply ironic ‘advertising posters’ for the Kotlas Railway, as if celebrating this important piece of Russian infrastructure. Kotlas was the last major stop on the railway that took Anna and other deportees to Siberia. It was part of the very important Perm railway that connects Central Russia with Ural and Siberia, and in 1917 Kotlas had been promoted to the status of a town in recognition of its position. The bright colours and buoyant feel of the posters contrast starkly with the menace of their messaging: ‘Siberia! Here you shall stay!’ These engines and trucks are not just transporting but cruelly deporting people, to a place where the Russian authorities will control their every move. Cargo trucks are deliberately made to look like prison carriages.

How does Diana’s focus here on the mode of transport help you to visualise this stage in her mother’s story of forced migration? What emphasis is placed on modes of transport in other, more recent representations of refugees and asylum-seekers?