In 1941, about 18 months after Anna Sokulska Forster’s family was deported from Poland, Hitler reneged on the pact he had made with Stalin and invaded the Soviet Union. Stalin changed sides, joining the Allies, and was persuaded to release the people he had deported to Siberia and to restore their Polish citizenship. A Polish army was being formed in the south and many families made their way first back to Kotlas and then a very long way south to the recruitment centres that were being set up in Uzbekistan and other countries in Central Asia. This journey often lasted over two months, changing from one train to another, and travelling through Kazakhstan to Tashkent and then further west into Uzbekistan.

Once in Uzbekistan, some of the deportees were allocated to collective farms and Anna’s family worked picking cotton, which was hard and dirty work, making their fingers very sore. Anna’s father went to a town called Kenimech to enlist in the newly formed Polish army and the family moved to an area nearby. They lived with an Uzbek family in a clay house. Uzbekistan is on the Silk Road, and Anna fed silk worms to earn her keep. Conditions in the army camp in Kenimech where Anna’s father was based were very bad, with typhoid and dysentery rife. The men were already in poor physical shape after 18 months in the labour camp, followed by two or three more on the arduous journey south from Kotlas. Many died, including Anna’s father. He is buried in the military cemetery there.

In 1942, after about 8 months in Uzbekistan, the newly formed army (the 2nd Polish Corps) and accompanying families were evacuated to Persia (now Iran). First Anna Sokulska Forster’s family had to travel to the port of Krasnovodsk in Turkmenistan to board ships that would take them across the Caspian Sea to Pahlevi in Persia. Many families were crowded onto dirty, coal-carrying steamers for a crossing that took three or four days; but finally they were out of Soviet Russia and were free. When Anna’s family reached Pahlevi, they and the other exhausted families were looked after by the British Army, which occupied Persia at the time, and also by the Red Cross. They stayed in British Army tents where they began to recover their health.

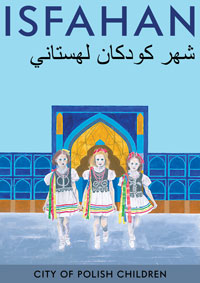

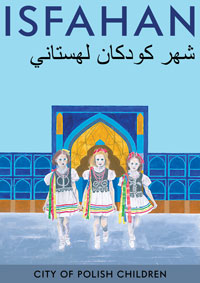

From Pahlevi they were next moved to Tehran, which for most of them was the first beautiful and peaceful place they had seen in three or four years. They finally had somewhere lovely to stay. Schools were established in the makeshift camps, staffed by teachers who had survived the forced migration. Many of the children, including many orphans, were still exhausted and ill and they were moved to Isfahan, where the mild climate could help them to recover. Many hospitable locals opened their homes (including some palaces) to accommodate them. Between 1942 and 1946 four schools were established in the city and Isfahan became known as the city of Polish children.

After a few months in Persia, the 2nd Polish Corps and their families parted company. The soldiers travelled west to fight with the British army in Italy and Palestine, while their families had to move on again since they could not continue to live in Persia. This time they would be sent to various countries throughout the British Empire to sit out the war. So another long journey began for Anna Sokulska Forster and her family, through Iran via Ahvaz – where Anna made a life-long friend of a young woman called Irena, who slept next to her on the floor of a warehouse. It was a hair-raising journey, on bad roads through mountains, to a port on the Persian Gulf where they boarded a boat to Karachi (at that point, in India; now, of course, in Pakistan).

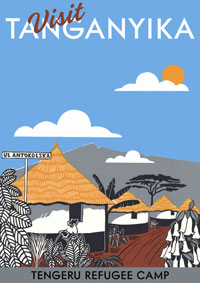

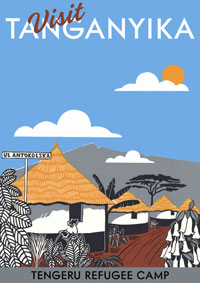

After a couple of months there, in early 1943, Anna, her mother and two young brothers boarded another boat and sailed for six weeks down the east coast of Africa to Mombasa in Kenya. From there they were sent to a camp in Tanganyika (now Tanzania) where they were housed in rondavels (traditional thatched huts) built for them by the local population under the British Authorities. The camp, Tengeru, was the largest in East Africa, with 4000 deportees. A farm was created, a church was built, schools were established and the families were able to settle for a few years in a warm climate with plenty of food. There were downsides in the form of malaria, snakes, and various unpleasant insects, but generally life was good.

To commemorate these different staging posts, as places of relative respite on her mother’s long migration, Diana Forster created these three posters. They are designed in the style of 1930’s travel posters, but the destinations were not chosen by the travellers nor enjoyed as holidays. The warm colours and beautiful scenery capture some of the pleasanter aspects of each location; but their cheerfulness and ‘holiday vibe’ are also ironic, designed to contrast voluntary travel to beautiful, exotic places with enforced and ongoing displacement, determined by forces beyond the travellers’ control.