In 2022, University of St Andrews undergraduate student Marios Diakourtis took part in a project to develop a virtual Museum of Peace. Having grown up in Cyprus, he has lived in the shadow of conflict and forced migration all his life; so he chose to explore a series of poems that reflect on the search for peace after war and displacement. The three poems he focused on were:

- The Ash That Travelled, by K.H. Miris

- Jasmine, by Nora Nadjarian

- Lament for Syria, by Amineh About Kerch

You can read some brief analysis by Marios Diakourtis of all three poems below. Marios is a skilled artist, so he responded to the imagery of these poets’ words with some pen-and-ink drawings of his own. As he explains in what follows, he drew on past artistic trends and symbolic imagery to capture some key aspects of displacement in his new artwork, particularly the trauma of loss, the challenges of journeying, and nostalgia for one’s old home.

The Ash That Travelled

Despite popular belief that the First World War ended at 11am on the 11th of November in 1918, many areas across the world had to deal with the ramifications of this conflict years and even decades later. Greece may have emerged victorious from WWI, the Treaty of Serves giving it significant gains in Thrace and Smyrna, yet the Greco-Turkish war that broke out in 1919 and lasted until 1922 would undo much of that. The end to that conflict came with the burning and subsequent destruction of most of the port of Smyrna in September of 1922. The fire started on the 13th of September and lasted until the 22nd, resulting in the loss of between 10,000-125,000 Greeks and Armenians and the displacement of hundreds of thousands more. The poem, ‘The Ash that Travelled’, written during the 70-year anniversary of the fire, is interested both in the memories of the event as well as the struggles that came with the subsequent displacement of the people of Smyrna. K. Georgousopoulos, also known by his pen name K. H. Miris, is a second-generation refugee from Smyrna, as well as a literary and theatre critic, filmmaker, and teacher.

The poem was written in Modern Greek; you can read my English translation here. As its title suggests, movement is a primary concern in the poem, and though the ash may be perceived as a signifier of destruction it can also be read as a remnant of conflict that must eventually settle down somewhere, much like the people who were forced out of their homes and into a new life across the sea. The majority of the poem is concerned with the days of the fire and the vain attempts of the residents of Smyrna to deal with the invasive smoke and ash. The poem plays with the ideas of boundaries and home, as the ramifications of the fire entail an invasion of this private, secluded space. The home represents a haven from politics and the public sphere, or at least the persona wishes it were so; but smoke and ash eventually enter the home and the residents of Smyrna are forced to evacuate their properties.

As the poem goes on, the ash continues to cast a shadow, literal and metaphorical – ‘sixty years now’. Peace for the people of Smyrna did not come with the resolution of conflict, but with time and a reluctant acceptance of defeat, flight and loss. The glimmers of peace that they find are dreamlike (a calmer counterpoint to the nightmares near the start), and they revolve around their memories of the city they left behind: ‘when we dream, we saunter in her orchards and cruise along her squares’. Like a phoenix, Syrmna and its people are reborn from the travelling ash: ‘one with our body, she flows in our blood.’ The poet describes how his beloved Smyrna was rebuilt on another coast, probably a reference to an area in Athens named Nea Smynri (New Smyrna). As the poem closes, he introduces the idea that residents have a moral duty to their lost city, with Smyrna said to be judging them as they go about their new lives in continental Greece. The lines of the metaphorical and the literal blur, as the physical reconstruction of the city in a different location is related to an almost dream-like recollection of spaces from the past that are emotional charged by nostalgia, identity, belonging and the idea of the home.

The fire at the port of Smyrna may have helped to end the Greco-Turkish war (itself a reminder that one conflict can often merge into another), but it sparked a new wave of loss and struggle for those affected. The speaker in the poem underlines that even decades later, true peace was not felt among the former Anatolians, as the bittersweetness in the heads and hearts of the refugees is the product of sorrow mingling with happy memories. The idea of singing confirms this, as melodising bitterness is on the one hand a way to cope with the pain, while on the other hand it is an accurate reflection of how positive and negative emotions can coexist in art. The poem itself attests to this, being at once an emotional conglomeration of lyrical lines as well as a painful reminder of loss. The poem constructs an intricate idea of peace, reflecting that for displaced people the absence of conflict does not bring a peaceful present. Rather, memories of a more peaceful past – elusive ‘pockets of peace’ – both stimulate and haunt survivors, as they try to create new lives in a new place which they fashion in the image of the old.

This emphasis on the ‘in-between’ experience of forced migrants is what inspired me to create the illustration accompanying the poem. It shows a woman standing between two ocean waves. On the right side, on top of one wave, stands a burning city with smoke billowing high, while on the left, there is a ship on top of the wave, and then another city from which trees appear to bloom. The female figure grapples between two cities and two situations, destruction and rebirth, conflict and peace.

Jasmine

… But the garden was not hers,

Jasmine by Nora Nadjarian

she was told. Nor was the aroma,

which lured and dared her to trespass.

Nora Nadjarian‘s poem ‘Jasmine’ was written in 2003, twenty-nine years after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974. (You can read the full text here.) It deals with issues of displacement and the insolubility of the Cypriot problem, both of which remain relevant to the Cypriot community today. On the 15thof July 1974 a coup d’état by the Greek Army in Cyprus, the Cypriot National Guard, and the Greek military junta of 1967 forced the then president Makarios to flee his presidential office in the capital, Nicosia. In response to that, five days later, on the 20th of July, Turkey sent its military fleet to the northern part of the island, claiming it was acting in the interests of the Turkish community on the island that was threatened by the coup. The campaign lasted until the 18th of August 1974, by which time the Turkish army managed to capture one third of the island with little resistance, the national guard having its own internal conflicts to settle parallel to this. The combined loss of this conflict is estimated to be at over 5,000 lives, with about 2,000-3,000 others being registered as missing. Their bodies still being discovered and identified up to this day. In addition, approximately 200,000 Greek-Cypriots had to leave their homes in the North, while about 50,000 Turkish-Cypriots were also forced out of their houses in the South, as the island was split into two, making Nicosia the only remaining divided capital in Europe since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Nadjarian situates her poem ‘Jasmine’ in the liminal space that physically separates one side of Cyprus from the other. As a refugee who has been forced out of her home but still lives on the same island, she embodies the bitter experience of all Cypriot refugees who have not entirely abandoned their country but must still face the bitterness of seeing their former home without being able to inhabit it.

Like other poems dealing with displacement, Nadjarian’s vision of peace cannot exist independently from conflict. For refugees, the search for peace in a new place is often bound up with traumatic memories that trigger thought of all they have lost. Memory is an integral part of this poem, as the sensory element is employed to transport the persona across space and time. The smell of jasmine is distinctly associated with the narrator’s family home, and it represents both the pockets of peace which refugees are capable of finding, even as they face a plethora of practical issues, and a fantasy of a past peace which they cannot access anymore.

The poem’s references to childhood play an important role. The narrator’s temporary return to childhood spells and hopes represents a fleeting, naïve optimism. The child whom the narrator encounters, ‘playing the fence railings like the harp’, sets realism against idealism: the real child in the poem (in contrast to the remembered childhood) is more accepting of the barriers now dividing Cyprus and treats them as part of their environment to play with. Many Cypriot refugees have died while hoping vainly for peace and reconciliation, imagining a grand return to their homes, their gardens, and their jasmine shrubs. Others have had to come slowly to the realisation that a diplomatic solution may not be reached within their lifetime.

From the poem, it can be inferred that the narrator’s father is one of those people who died while still hoping for a return – or perhaps even as a victim of the conflict itself. The narrator herself is not so much hopeful as determined and rebellious. In the poem, she attempts to traverse the line that separates Turkish-occupied territory from the rest of Cyprus, entering the UN buffer zone which still exists today as a no-man’s land. The year this poem was written has significance, since 2003 was the year when some access points on the buffer zone were opened for the first time since 1974, allowing people to temporarily cross the ‘border’ and thus giving refugees the opportunity to see their old homes up close, albeit briefly. Though this did little to curb the bitterness felt by many Cypriots from both communities, the increased interaction between Greek-Cypriots and Turkish-Cypriots is a glint of hope gesturing towards the potential unification of the island. At present, as in the poem, blue-bereted soldiers continue to monitor all interactions – an indication of how fragile even this glimmer of peace is.

Among other things, this poem reminds us that peace is not simply a state or condition that prevails in the absence of ‘hot’ conflict. Refugees carry the trauma of war within them, and while they must create a new home for themselves in a new place, the peace they create rarely feels complete, nor does it feel permanent. They are often waiting for some kind of home-coming, whether that be a return to old places or the re-growth of bits of their lives which the conflict had shut down. Peace amid displacement involves the sweet anguish of intangible memories, and a process of learning to live with new borders and other people’s rules.

However, this poem also teaches us how empowering it can be to remember past peace or visualise a more peaceful future. It energises the poem’s narrator. For people whose memories are full of exploding bombs and death, it is important to make space for the smell of jasmine in the garden, a symbol of harmony that – while sometimes barricaded and inaccessible – thrives as a precious memory in the minds of refugees, giving them hope for a peace that is yet to come, amid a conflict that is decades old.

The imagined confrontation between the narrator and a blue-bereted UN peacekeeper, and the narrator’s need to override that peacekeeper’s attempt to stop her ‘crossing the line’, invites us to reflect on the different between ‘top-down’ peace keeping and the slow, difficult, intensely personal process of finding or making peace again as individuals after conflict. Peace amid displacement, this poem tells us, is about cycling between hope and nostalgia, naivety and realism, optimistic anticipation, and the ongoing trauma of loss.

The illustration I created to accompany the poem highlights ideas of the boundary and division, as the figure is positioned against a flowery background on the top, while below, military paraphernalia populate the picture. Learning to live with those contrasting imageries always present has grown to be a casual part of the lives of people in Cyprus, as duality and division inform the new state of peace of the island.

Lament for Syria

Oh Syria, my love

You can hear Amineh Abou Kerech reading the full poem here.

I hear your moaning

in the cries of the doves

As of the 15th of March 2022, the conflict in Syria completed its eleventh year. Starting as a pro-democratic peaceful protest in 2011, what has developed into the Syrian civil war has claimed over half a million lives according to current estimates, and the death toll goes up daily. However, the situation in Syria is more than a civil war, with many other countries feeling its ongoing ramifications. Some nations actively participate in the dispute; Russia and Iran in support of the Syrian government, while Turkey, the West, and other Gulf States have intervened in support of the opposition. Meanwhile, many other countries across the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Europe have faced and are still facing one of the largest refugee crises of recent history. Of the pre-war population of Syria (22 million), over half of these people have been displaced, either internally or externally.

Amineh Abou Kerech is one of these people, forced as a teenager to transition from childhood to adulthood while also moving from peace to conflict to refugeehood. She fled her homeland in 2012 for Egypt, before eventually moving into the United Kingdom. Her poem ‘Lament for Syria‘, written when she was just 13 years old, won the Betjeman Poetry Prize in 2017 for its poignant and insightful perspective on the Syrian conflict.

Written while Kerech was still trying to grapple with the realities of leaving behind a home country torn apart by war, this poem is a poignant reanimation of Syrian values imagined through the memory of a thirteen-year-old girl. Kerech understands that her country is currently at war, yet she longs for peace and dreams that through her poetry she might be able to help heal Syria. As well as trying to visualise or engender peace for her country, her final stanza also hints that she is trying to find some kind of inner peace in the place she now lives. She wants a peaceful ‘homeland’, both for Syria and herself.

The vision of the doves, a traditional symbol for peace is here ambiguously employed by the poet, as their crooning is what launches a poem that will tell a story of war while advocating for a solution towards peace. The fact that the doves are Syrian and are at the time of the poem above the persona’s head suggest that either she is still back in Syria, or that the doves, or at least the idea of them, have travelled with her across borders. This idea of reinventing something familiar is common in stories by refugees, as it follows the trope of getting the person out of the place, but not the place out of the person.

For Kerech, the cries of the doves are conflated with the cries and moans of her personified county as ideas of peace and conflict are coalesced, ultimately creating a sensory cacophony that is meant to invoke a sense of urgency to the reader. But that is not all. Kerech is not only interested in presenting a current image of Syria that is ravaged by bombs and death. Instead, she turns to pockets of peace from the past, sharing some well-cherished instances from her memory that are representative of the virtues of Syria, even as the world cannot see them because of the war. Ideas of respect, family, community, and the reverence towards bread as a symbol of sustenance, are but a few reminders of what a peaceful Syria looks like, and the fragrances of coffee and jasmine help in bringing those to life.

An implicit question in her poem is whether or not these pockets of past peace can be revived. Her poem also invites us to ask: can poetry itself bring peace? Despite the sights and sounds of war, her verses conjure a vision of a country and culture that has great potential for peace in the future, not just a peaceful history. This vision perhaps brings the author (and reader) some respite and inner peace; but the poem is also about home-(re)making and city-(re)building, and poetry itself seems bound up with that endeavour. On the one hand, it represents the lone lament of a refugee girl whose country has been trampled by soldiers; on the other, it shows us that Syria’s spirit can be reanimated and peaceful times can be revived by the power of the pen.

The poem closes with Kerech addressing the reader, the global community, or basically anyone who cares to listen, as she asks for help in imagining a new ‘homeland’ that is pretty much like the old Syria, a peaceful place where people are not afraid to live and a place Kerech may one day be able to return to. Her appeal for help combines past and present, Syria and not-Syria: she ends the poem in a liminal place, hovering between old and new, war and peace.

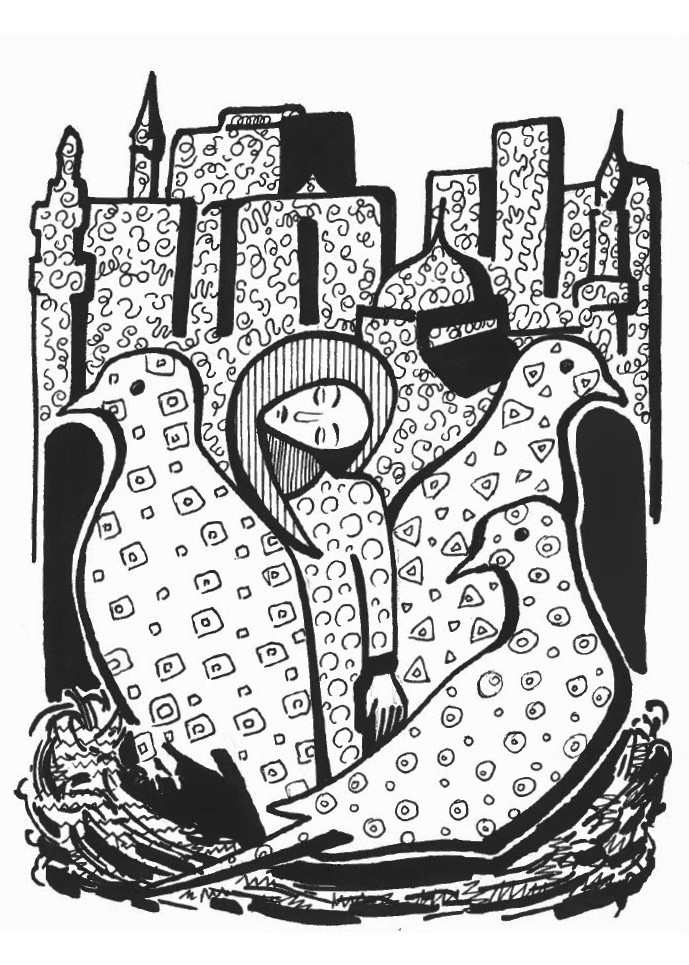

I have tried to capture that idea of liminality in the illustration I drew to accompany the poem. The dove’s nest highlights the idea of home and belonging, which the skyline of Damascus in the background helps to pinpoint geographically. The depicted figure is thus positioned between the crooning doves and the memory of Syria in her search for peace, as she is forced to ‘build her nest’ elsewhere.

Drawing Displacement

Opting for black-and-white ink and marker illustrations, with a distinctly abstract approach, I am first and foremost citing Picasso’s Guernica, one of the most influential war paintings to be created. Picasso used the freedom and abstraction of modernism to show the complexity, chaos and atrocities of war, but I think that war’s aftermath can be just as complex and convoluted, hence I chose to follow a similar style. Throughout the course of our research for the virtual Museum of Peace, we have critiqued habits of visualising peace as simply the binary opposite of war. I deliberately adopted a colour scheme that would evoke but also question such ‘black-and-white’ distinctions; the different degrees and styles of shading in my drawings are designed to nudge the viewer into look beyond what is superficially suggested and read between the lines and the black-and-white aesthetics.

Your might notice that some graphic patterns are purposefully consistent between the three illustrations. I wanted to convey some meaning with this. The symbols of peace – namely the doves, the jasmine florets and the trees – are patterned with geometric shapes that are whole and fairly similar in appearance, ranging from squares and triangles with smoothed angles to circles. I drew inspiration for these patterns from Nihad Al Turk, a Syrian painter currently active in Beirut. Though his compositions are much more colourful than mine, I really appreciated the intricacy of his style, and wanted to incorporate an element of his art into mine to ensure that my illustrations are both thematically and artistically positioned in the Eastern Mediterranean. The other recurring pattern in all three of my illustrations can be found adorning all the figures that are reminiscent of war and conflict; the gun, helmet, and guard post for ‘Jasmine’, the skyline of Damascus ravaged by war for ‘Lament for Syria’, and the fire and smoke for ‘The Ash that Travelled’. This pattern is intentionally more disorganised, the shapes being incomplete and unpredictable, which is something I wanted to contrast to the more harmonious pattern adorning the different symbols of peace I previously mentioned.

The similarities but differences between more harmonious and more disorganised patterning are designed to prompt reflection in the viewer. My aim is to show that experiences of peace and war can be synchronous, and they may even be found in the same composition. This is exactly how all the poets I have read visualise peace for refugees and forced migrants: as liminal figures that mediate between conflict and peace.

The final influence on all the illustrations I produced is the work of Xanthos Hadjisoteriou, a Cypriot painter active in the 20th century, who pioneered the figure of the woman with her eyes closed and head turned towards the ground. To me, his style is reminiscent of Greek Orthodox depictions of the Virgin Mary, whose face is depicted with a similar simplicity and emphasis on her large eyes, a motif that corresponds to how she has witnessed from up close the great miracle of the birth of Jesus. The choice to leave the eyes closed is therefore another probing feature I wanted to include in my illustrations. It cites an artist that is close to my upbringing, while also urging the viewer to think about why the woman may be averting her gaze and closing her eyes. Is peace the grand miracle that will make the woman open her eyes? How many people, be they refugees or not, are waiting to see this?