The last major railway station on the freezing journey from Poland was Kotlas in Arkhangelsk (Archangel region). This was not the end of the journey, since Anna’s family travelled on for a few hours to a labour camp (or posiolek) called Kopytovo which consisted of bleak barracks with families sharing cramped living space. There they endured more dreadful conditions, with little possibility for hygiene. They were plagued by bugs and vermin that multiplied easily in the barracks.

Fed starvation rations of bread, they received little or no medical care, and had to work in the surrounding forests in temperatures of -40 degrees Celsius, cutting down trees, sawing them up and taking them to the river to be transported to wood mills downstream. For this they were paid a pitiful monthly wage, 10 per cent of which was deducted for camp administration. The work was dangerous, particularly for those preparing the logs for transportation down the river. One day Anna fell into the freezing water but fortunately came to the surface away from the logs. If she had surfaced beneath them she would probably have drowned. She was allowed to return to the camp for the rest of the day, a rare gesture of humanity.

Any transgressions by the deportees were liable to a fine or a few days in custody. Being twenty minutes late for work could result in three months of hard labour and a 25% deduction of wages. The harsh conditions resulted in many deaths and Anna’s father, a carpenter by trade, made coffins.

The deportees exchanged possessions they had brought with them for food. In the summer they could collect berries and wild mushrooms in the forest, but scurvy and night blindness were common due to the lack of vitamins. The camp guards grew cabbages, which of course were forbidden to the deportees. However, Anna and some of the other young people crawled on their hands and knees at night to nibble the cabbage leaves. In the morning the guards assumed the damage was made by animals so no one was punished. At the beginning of their time in the camp, the family received parcels from Anna’s aunt, who had not been deported. These contained flour with eggs carefully packed into it; but they stopped arriving after a while.

There was a primary school in Kopytovo, which Anna’s two younger brothers attended. One of them could have got the family into serious trouble when he wrote a rude verse about Stalin on the blackboard. Fortunately, the teacher went directly to Anna’s mother about it. Poor George was beaten so he wouldn’t do it again.

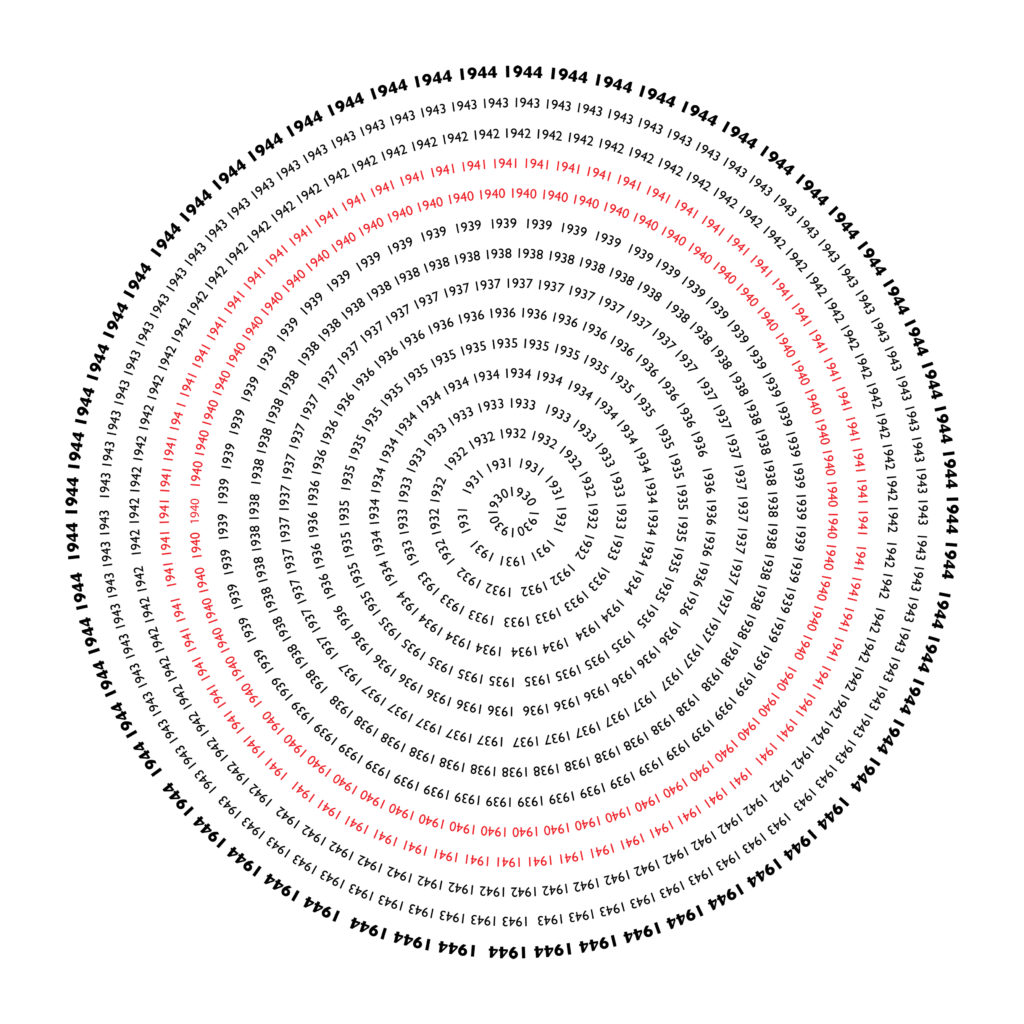

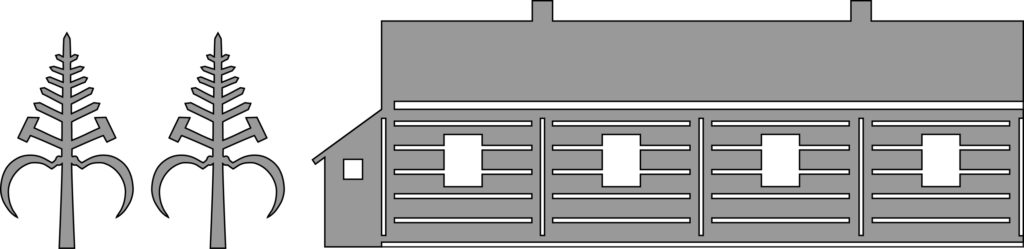

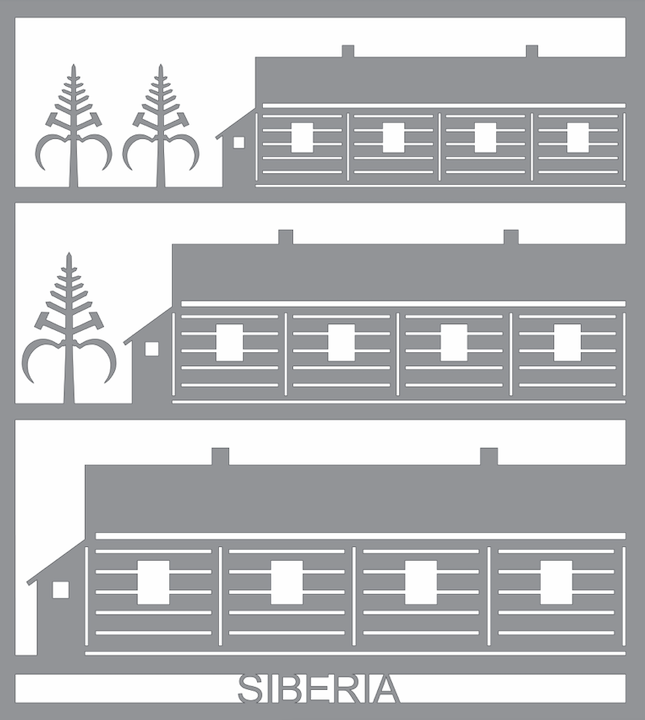

Diana Forster has depicted the harsh conditions in Kopytovo camp in some of her previous artworks, particularly through a set of birch wood-cuts entitled ‘Siberian Exile‘. These beautiful panels (which again employ the Polish craft of wycinanki, and are designed to cast shadows suggestive of menace and war’s legacy) contrast with a series of ironic posters which Diana has designed, ‘advertising’ the labour camp in a parody of Soviet-era propaganda. She has also created a haunting set of works based around the Siberian forests where prisoners were made to work. Sinister ‘gulag trees‘ crop up in several of her pieces, including Panel 4 in Somewhere to Stay; and her ‘Tree Rings’ marks the deadly passing of years (1940 and 1941) for prisoners who laboured, lived and died in the forests.